Monday Mailbag #59

/You’ve come up with a bunch of different terminology in your time writing this site (Imps, Reps, etc.). I think you need a word for a trick that magicians are really excited for but laymen care much less about. And for that I would go with “Cog.”

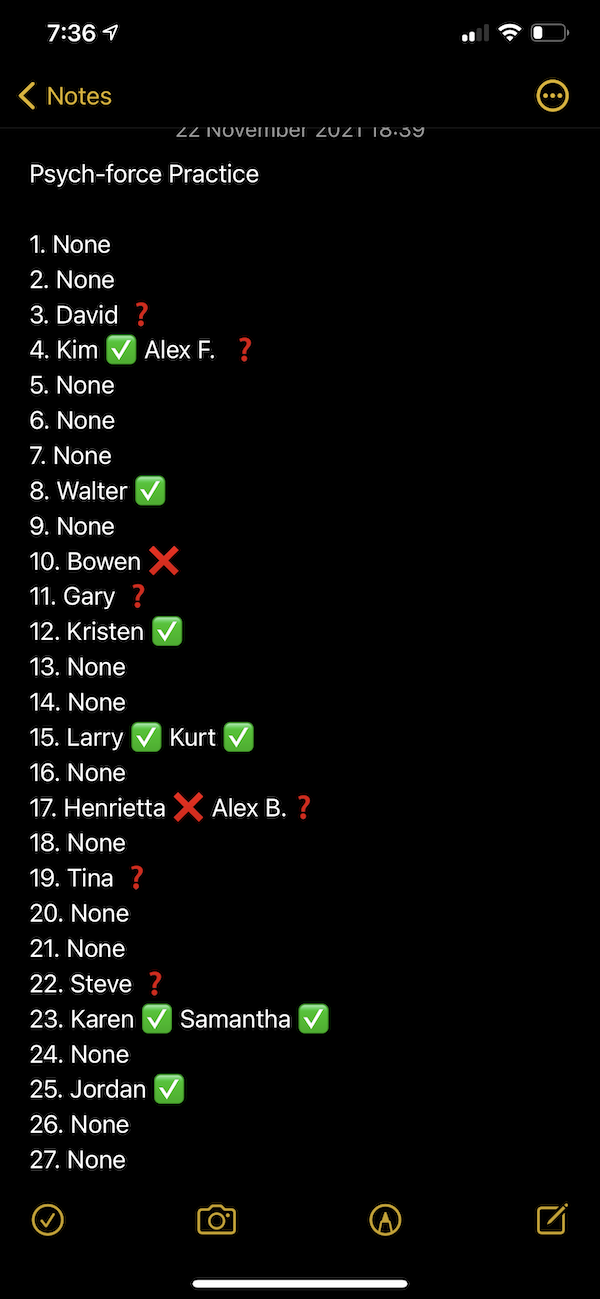

This is based on the Cognito App which all of my magic friends have been amazed by, but the laypeople I perform for have been underwhelmed by. It doesn’t get bad reactions, but it rarely gets great reactions for me either, except from other magicians. I’ve even had some laypeople suss out the general idea of the binary principle. Not down to the mathematics but the idea that knowing which photos they say yes to would allow you to know which card they’re thinking of.

Do you have any ideas on how to bring the focus off the phone when using the Cognito App? — LH

No, I don’t, I’m afraid. As I said when I originally talked about this app, the issue I see with it is that it requires a lot of energy to be focused on the phone. To pull that energy off the phone and make it about something real between the people taking part in the interaction… that’s going to be hard.

The issue with using the app to find out what someone is thinking is that it requires a lot of, “Is your card in this picture? Is it in this picture? Is it in this picture? Is it in this picture?” This is the dull, uninteresting part so people try to rush through it. Understandably. But if you rush through the dull, uninteresting part, you’re suggesting to the spectator that this is actually the important part (method wise). If it wasn’t important, you wouldn’t include it, because it’s dull and uninteresting.

So, counterintuitively, what you might want to try is to focus more time on this part of the process. By focusing more time on it, and adding some creative elements to it, you can make it feel like more of a theatrical necessity rather than a methodological necessity. I don’t know if that would work, but that’s what I would try.

Other that that, I will again say that there are likely to be very few really cohesive plots and premises that make a ton of sense with this app (and the process of looking through multiple photos). It’s probably a better use of your time to identify the two or three premises that work really well, rather than trying to use it to solve many magic problems. For example, is this ACAAN procedure using the app (which involves a meaningless, unrelated “observation test,” and a meaningless, unrelated “estimation test,” before getting to the ACAAN part) a step forward in ACAAN methodology? In my opinion, no. You can say, “Yes, but the spectator never has to name their card!” Okay, but they have to do a bunch of other junk you don’t have to do with other ACAANs. And I’m not sure the trade-off is worth it. That, I feel, is an example of using the app for the sake of the app, not because it really makes for a better trick.

Finally, on the subject of this app, supporter Jonathan FC wrote the following which I think might have some merit:

I think it could also be used with your transgressive anagram philosophy.

By this i mean, use the cognito procedure, like a failed attempt of mind reading. Ditch it. And then once you have the peek you can go for a more interesting presentation.

Will you be buying your boy Josh’s new matching deck effect? If so, will you tell the story of his parents meeting as it was the story of your parents meeting? —AS

No, I won’t be getting that trick. I think it’s a great trick for certain performance situations, and I enjoy the story Josh tells with it. And I have no doubt a lot of people will get a lot out of it. My performance style is too casual for it. And my friends are the type who really want to prod the mystery to see if it’s completely airtight and they would definitely look at the spread of cards at the end to make sure everything was copacetic, and you can’t really have that. Plus I have my own deck matching effect I already do.

But if you are going to do the effect in a situation where people don’t know you, you can probably steal Josh’s story and not have to worry about not getting away with it.

If you don’t want to take that exact story, you can easily create something similar. All you need to do is come up with some arbitrary circumstances and plug those into the story. “If his shoelace hadn’t broke, he wouldn’t have had to stop at the store,” blah, blah. If you can’t plug in your own details that you create into that format, then you’re close to braindead. Go ahead and just steal the story of how Josh’s parents met, because your parents did have any kids that lived, apparently.

Your post about how Mentalists reveal information was very timely. The previous week, at an Elder’s meeting, a performer did a routine with this type of finish, where you reveal what you have read in the person’s mind. And my comments to him were all about the reveal, and your post made the rounds and produced lots of good thinking. So thanks.

I remember when I worked on the staff of a Sitcom, we talked about beats. Basically this meant any moment where a character has any emotional reaction. Big or small, happy or sad, annoyed or pleased. Anything.

One main goal of reviewing the script this way was to make sure that we did not repeat a beat, unless it was to specifically set up something based on the repeat. But if character A displays some annoyance at something character B did, and they repeat it, it can not be the same annoyance. It has to be bigger, or the target has to be slightly different, but it has to be moving in some direction.

This was what I didn’t like about that performer’s presentation. He got a fact, then he got another one, then he got another one, until he was done. Each moment was impossible, but they were all exactly the same beat.

So I think the reveal has to have its own arc. It has to go somewhere.

I find thinking about “beats” like this is a useful way to improve these sections.

And not just in mentalism. How many ace assemblies or coins across routines have the exact same beat three times in a row? —PM

Yes, good points here.

I don’t mind too much if the “beats” are the same, so long as that’s done to set a pattern that is somehow broken in the climax of the trick. But yeah, usually it’s just, “This coin went from one hand to the other. Then this one did. And this one did. And also this one did. The end.”

However, for me, the even bigger sin—going back to the idea of mentalism reveals—is when there’s just a straight line between each reveal and the ending. It just makes for a dull story with no climax.

It would be like if you were watching a mystery movie or reading a mystery novel and halfway in the detective determines the killer is a man, then a little while later that the killer is in the same neighborhood, and then that the killer lives in the house next door. If that’s how the book progresses it’s not going to be very interesting at the end when he’s like, “And the killer is… the neighbor!” Like yeah, we know.

However if the detective remains silent throughout the book, or he appears to be grasping at straws, or if he’s clearly on the wrong path, then it becomes interesting when the pieces fall into place at the climax. That’s the approach I was recommending in that post.