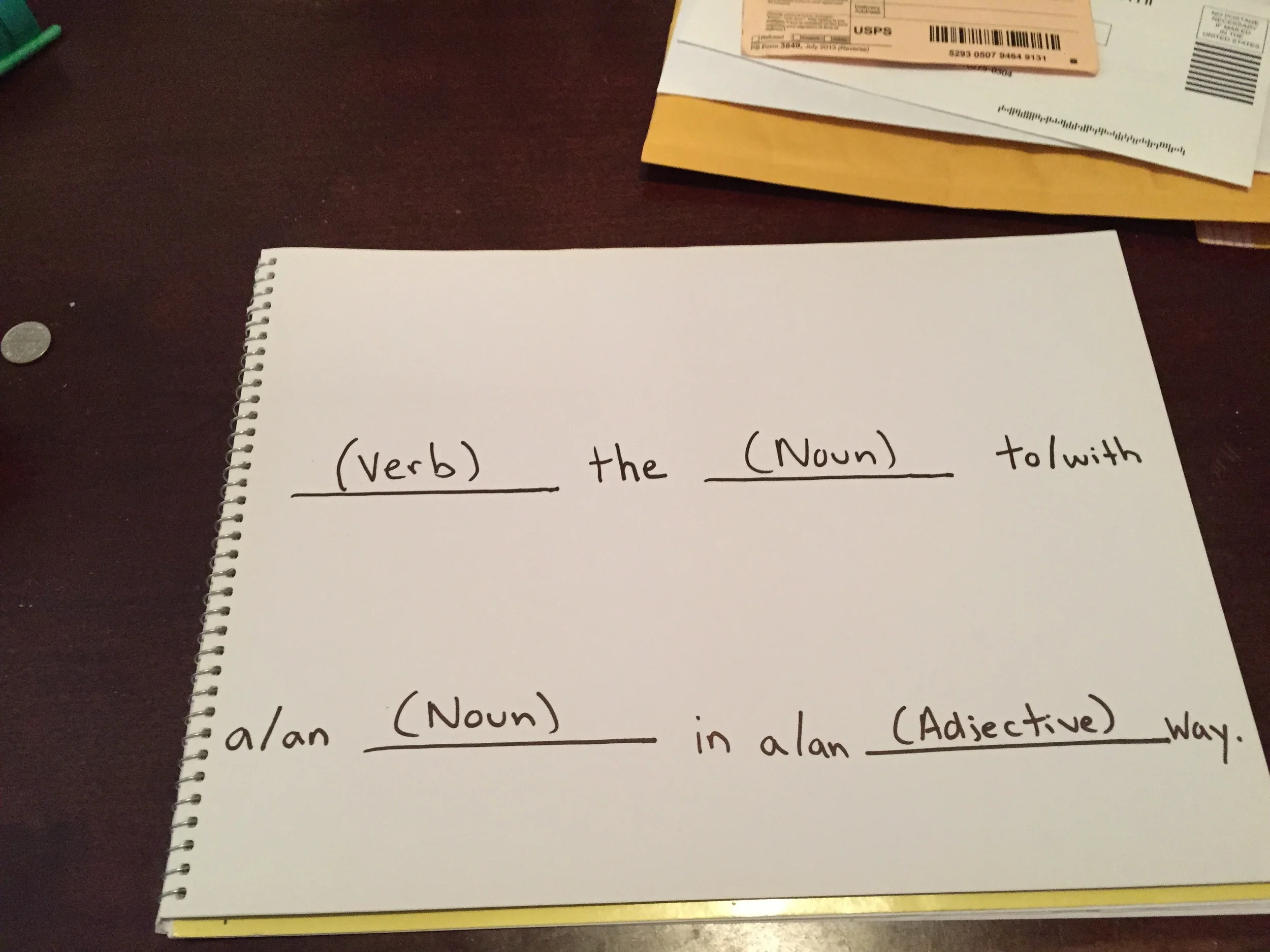

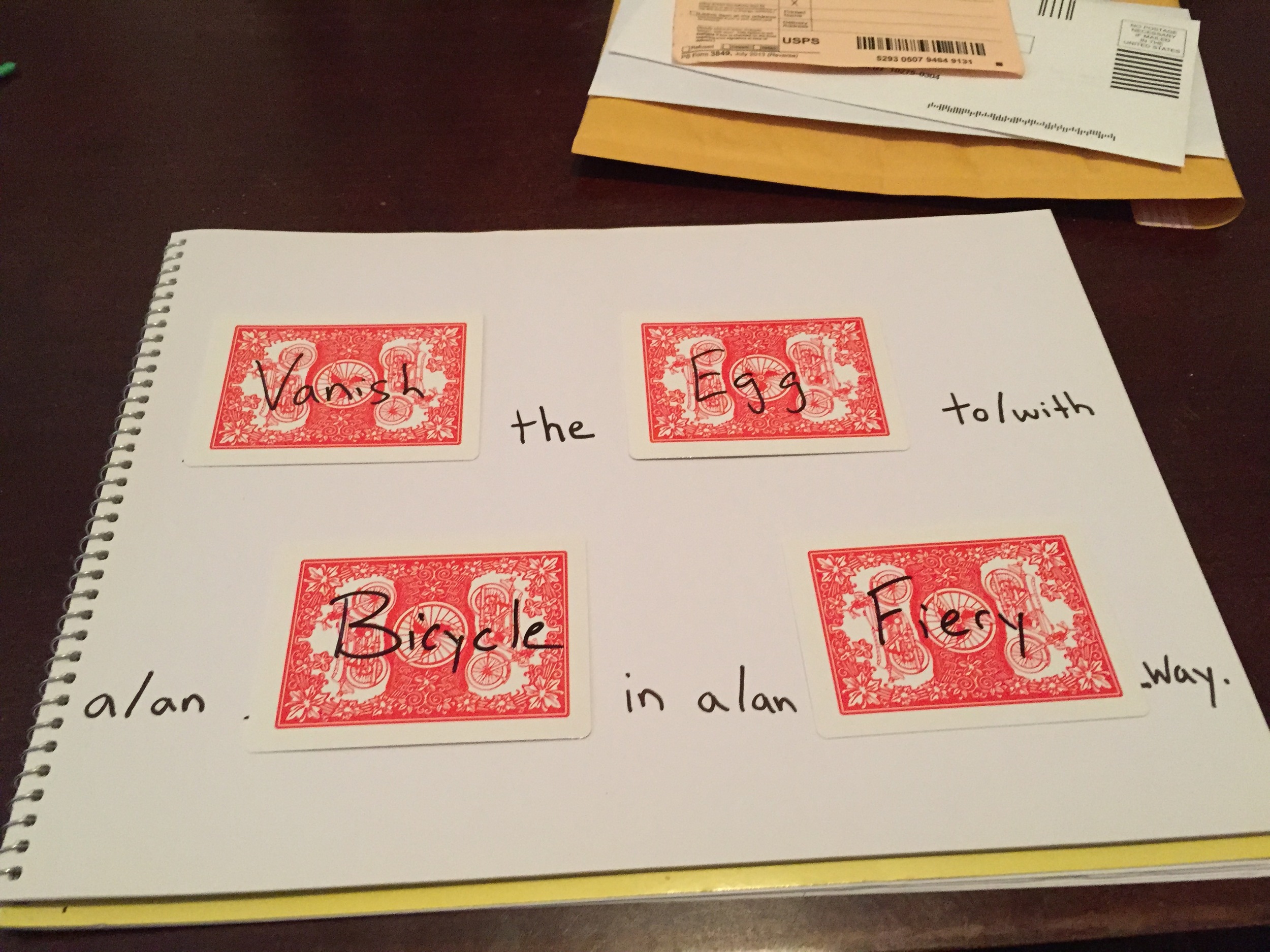

Part Three: Now they are seeing an actual magic trick. Vanishing an egg with a bicycle. Or making a bowling ball appear from a pizza box. Or tearing and restoring a skateboard with a puppy. Whatever. It should be a seriously incredible trick. I would not go creating a half-assed trick with random items just so you could do this larger presentation. Wait until you have a real mindblower that's strong enough to stand on its own, then incorporate it into this performance piece

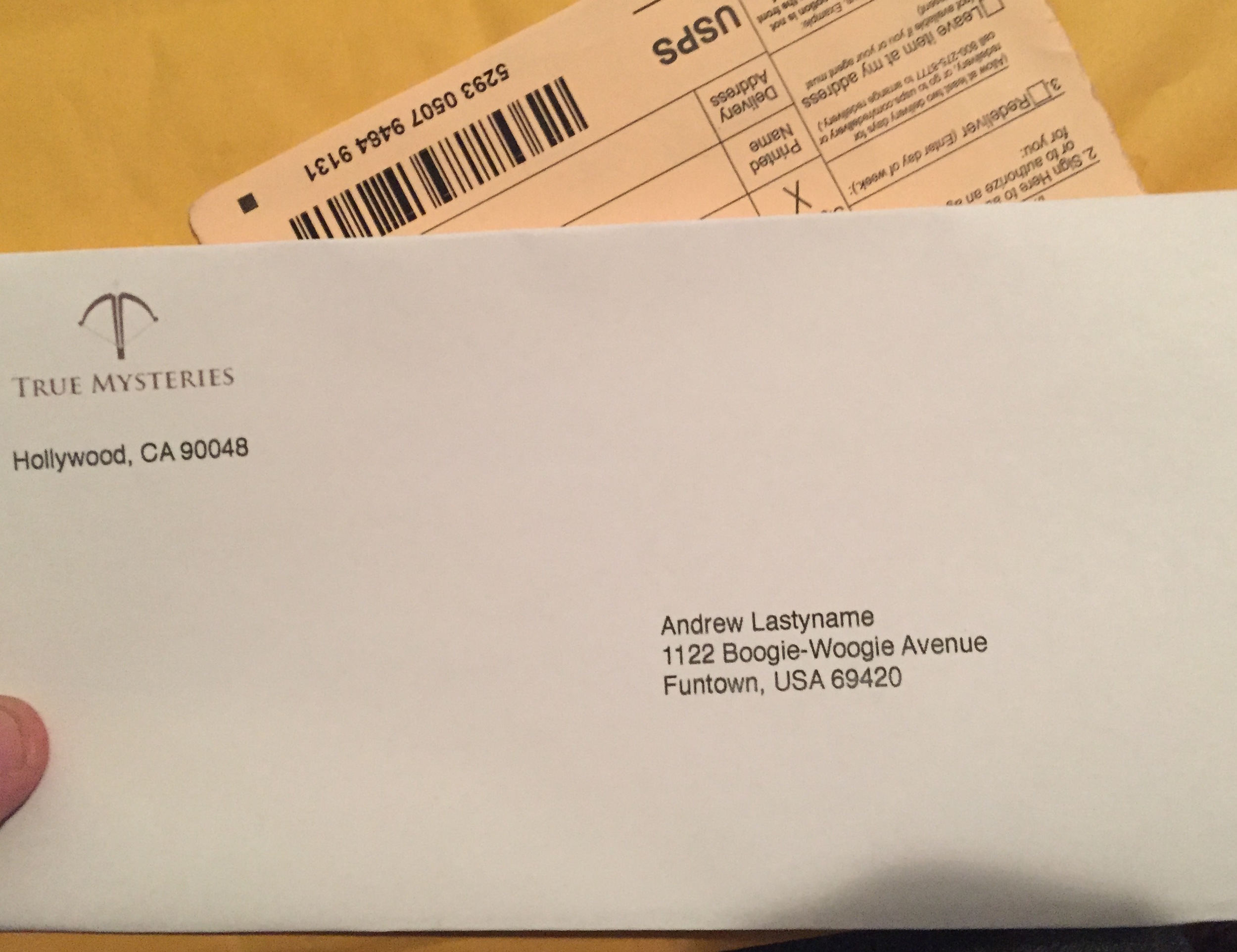

Part Four: After witnessing a truly strong magical performance, the twist ending transforms the nature of the entire experience. I would not just pull out a prediction at the end and say, "I knew what cards you would name." That's a little too dull and a little too much of a fuck-you to the premise you established. Instead, by making it a wild coincidence (as opposed to a prediction), the other three "movements" still stand on their own within the context of the trick. If you could "predict" what cards they would name (and thus what words you would end up with), then the part where you're brainstorming ideas would just be a nonsensical waste of time. This is not to suggest the audience will really believe in this mail-order magic blueprint company that just happened to send blueprints for an effect that was seemingly created on the spot. They understand it presents the same impossibility as a "prediction." But by not treating it like a prediction or claiming responsibility for it, the integrity of the story of the complete piece makes sense.

Examinability

After the words were picked originally, you have the word-deck in your hand. The four cards are turned over and the sentence is unveiled. You then get up to go get the items mentioned on the backs of the cards. When you're in the garage getting the bike (or whatever), you have all the time in the world to swap out the force deck for a normal 52-card deck (that is similar to the Phil deck in its distinctive quality) that truly does have random words all over the back. You remove from that deck the 4 cards that were named by the spectators. Then when you return to the room, you just place that deck back on the table. As far as the audience is concerned, that deck's purpose was complete minutes ago. So they won't even notice you leaving and returning with it -- it's a completely natural action.

Now this is an incredibly strong convincer after the twist is revealed because they can now pick up the deck and examine everything and nothing is amiss. No other cards would have created that effect or matched the blueprint in the envelope.

You might think they'll think something is up with the 52 cards of a Phil deck. They won't. If the cards are not in a card case, and are just spread around on a table, the deck seems full enough. If anything they will just feel like cheap cards to a spectator. If you're concerned, when you introduce the deck in the beginning you can say you got it from a dollar store, but the cards were too cheap to use regularly so that's why you're writing on the back of them for this trick. But it's not necessary unless you're performing for someone who handles playing cards on a very regular basis. (And just to be clear a Phil deck is not the same thing as a "Double Decker" deck. 52 cards of that type would not withstand handling by the spectators.)

The Non-Phil-Deck Method

This presentation allows you to use a regular deck, if you want. I don't know that I would, but it would be easy enough to and it could almost be handed out for examination -- at least in a more formal performance where audiences tend to give things rather cursory examinations. It would still need to be switched to have a fully examinable deck at the end, but could withstand a brief examination at the beginning.

You have to exercise a bit more control on which card everyone thinks of, but with this presentation, where different cards have different types of words (and you need particular types of words) I think the limitations make sense.

So you say to four people, "In a moment I want you all to think of a value of a card. Not a suit, just a value. I don't want you all to think of the same value because that would be too easy [whatever that means]. So you two, [indicate the people to your left] think of an odd value, and you two think of an even value. We need different types of words. The verbs are on diamonds, so attach your value to a diamond. The adjectives are on hearts. You'll be our adjective person so whatever value you are thinking of make it a heart. [You address these statements to the people on your left.] The nouns are all clubs and spades. So make your card a club, and your card a spade. Got it?"

Then they name the cards they were thinking of and you're ready to go.

So let's look at the breakdown of the deck and you'll see why it works especially well in this presentation.

First, there are 28 cards they can't name (even red cards, odd black cards, two jokers), on these 28 cards you will write 28 random words. A mix of nouns, verbs, and adjectives. These cards can be freely shown to your spectator. On the seven odd diamonds you write adjectives, but they should be seven different adjectives that could all apply to the trick. In the example, I used the force word "fiery," imagining an egg vanishing in a flash of fire. But you can easily imagine other words that would apply to that type of trick as well: hot, bright, dangerous, quick. And then you can add some adjectives that just require you to embody a particular attitude: sexy, funny, mysterious. With seven different adjectives we now have 35 cards that can be freely shown. With the four actual force cards/words it's 39. And then if you can think of any synonyms for the nouns and verb you're using (disappear instead of vanish; bike for bicycle; food or breakfast for egg), you can easily have about 42-45 cards that you can freely show. Think of that. You can cleanly display about 80-90% of the deck and yet it will force one very specific trick with four "freely" thought-of cards.

Stage Version

This would translate amazingly well to stage. Imagine this. You come out on stage and talk about this creative exercise you used to do with a deck of cards and random objects. And you talk about how much you liked this exercise because it was always challenging and kept you in the moment. And at first you thought of it as more of a mental exercise, but now you realize that it deserves to be put in front of an audience. "These cards can create over 100,000 different trick descriptions. So that means that what you see tonight will not only be a first for you, but it's also a first for me, and because of the randomness it will be a first for anyone ever. A brand new trick that has never been performed anywhere."

Onstage there is a small mass of items. "I asked the stagehands to assemble some items from backstage. We have wigs, pillows, framed posters, a can of beer, instruments, and so on. They also wrote the names of the items on these cards as well."

You go through the selection procedure and get the sentence: PENETRATE the MANNEQUIN with a UKULELE in a DANGEROUS way. "Hmm, this should be interesting," you say. You sit at a table on stage for a few minutes (yes, actual minutes) just thinking while a live cellist plays for the crowd. After a few minutes you bolt up and start moving things around on stage. Once everything is in place you proceed to penetrate a mannequin with a ukulele while standing on one leg on a skateboard with thumbtacks all over the ground. The audience applauds wildly.

You step down and accept their applause. Someone comes out and sweeps up the thumbtacks. "Thank you, ladies and gentleman. That means a lot to me. You know, I come from a magic family. My great-great-grandfather was Brooks the Magnificent. And while you might think for a lover of magic like me that would be a blessing, I have actually spent a long time living in his shadow. And Brooks the Magnificent casts a large shadow. My family did not encourage me to practice magic. We are pretty much estranged now. And before we were I was constantly being compared unfavorably to my great-great-grandfather. So to be able to come here and perform something like that -- an original miracle that has never been seen before -- well, that means the world to me.” You start putting the props back on the prop pile. "It's actually almost life-affirming, in a way. My great-great-grandfather was an incredible magician, but not a great man, and the ramifications of that are still being felt in my family today. So to be able to do something he could never dream of accomplishing means so much to me." As you're returning the items one of the poster frames that was leaning against the pile falls backwards on to the floor. For the first time you see the face of the poster.

"What the FUCK?!" you scream.

You hold up the poster to the audience. It's a handsomely painted old-time magic poster that reads, "Brooks the Magnificent presents 'The Amazing Ukulele thru Mannequin Penetration!'" With an old-timey guy in a tux balancing on one leg on a skateboard and penetrating a mannequin with a ukulele while some ghostly spirit looks on approvingly.

The performance ends with you running off stage and the sound of a gunshot behind the curtains.