100 Trick Repertoire Redux: Part Two

/I ended the previous post in this series with the statement that my next post would contain, “my current way of maintaining my 100 Trick Repertoire in a manner that keeps the tricks fresh in my mind while minimizing the time I need to spend practicing.”

That’s going to be the focus of today’s post.

I’m not someone who likes practicing. One of the first things that made me feel like I didn’t fit in when I was spending time with other magicians happened at a small magic convention I attended as a teenager. There was a group of magicians that I didn’t know having a conversation that I had somehow wormed my way into. At some point they mentioned a magician—likely someone well known in magic circles, but not anyone I knew of at the time—and one of the guys was saying how this magician practiced the bottom deal or the pass or something for hours a day for years. And I looked around and I was like, “Heh… what a dork.” All their eyes turned to me. I soon realized that wasn’t the point they were making when they were like, “Well, now his pass [or maybe his bottom deal] is invisible. That’s what you have to do.” And I was shamed into agreeing with them and quickly backpedaled like a total pussy. “Oh yeah, definitely,” I said. “You have to.”

But now I feel no shame about thinking that practice sucks. I mean, if you find working on sleights and moves to be meditative or fun, then that’s great, knock yourself out. But if you don’t, then you just need to practice enough to keep your working repertoire fresh and at the top of your mind.

Of course, this might not be true for you if your goals are different than mine. If you want to be a world-class card cheat, then you’ll need to put in a lot of work. If you want to have a premier manipulation act, then you’ll need a lot of practice. If you want to be a master coin magician, that’s going to require you to devote a ton of time rehearsing in front of a mirror.

But I don’t think of those things as goals of the amateur. Those are professional ambitions, or at least magician-centric magic achievements. Myself, and most of the amateurs that are drawn to this site, are just looking to use magic in a way that keeps themselves and the people they perform for interested and entertained. And that doesn’t require a ton of traditional “practice.” Yes, you need to master the moves required for the tricks you want to perform. But you can come up with a full 100 Trick Repertoire of strong magic that requires no moves, if you’re so inclined. So the minimum amount of time needed to master sleights is really up to you.

Similarly, a magician performing in social situations is usually not going to want to have a full script memorized by heart. She may have some beats she knows she wants to hit during her performance. But memorizing a few beats is much less of a time commitment than memorizing pages of scripting and trying to keep that in your long-term memory.

The nice thing about being an amateur magician performing in social situations is that it doesn’t require a huge time investment to do it well. Rigidly sticking to a script you memorized word-for-word is not valued in social situations. And, in my experience, the type of magic that requires the most amount of practice, is often the type of magic that goes over most poorly in casual environments. I’m pretty well convinced that I could take a mildly-charismatic non-magician and teach him three tricks/presentations over the course of an evening and put him up against any FISM winner doing his card manipulation act that he spent 12 years perfecting, and have them each perform for 15 minutes at a house party and 95+% of the audience would prefer my guy.

Spending 100s of hours on a center-deal will provide you few rewards when performing casually.

What is rewarded in social performing is having a large repertoire and being able to nimbly present a wide variety of interesting moments to people depending on the situation

Building up that repertoire does require a lot of time spent researching tricks and learning the methods and coming up with some presentational angles for them. But there’s no hurry to do that.

Once established, I believe you can maintain a large repertoire—even one with 100 tricks—in just a few minutes a day on average.

The way to do this is to not have a set frequency for how much you practice your repertoire. Instead you want to focus your time on the tricks that are giving you issues, and not waste too much time on those that are second nature to you.

In order to handle this automatically, I use the concept of “spaced repetition.” This is a way of learning and remembering things that automatically focuses on things that are new and/or difficult for you.

I use a program called “Anki” to manage my repertoire practice. It’s a flash-card program that uses spaced repetition. I’m not going to walk you through how to use the program, because that sounds boring to me and you can figure that out in other places. But I’ll tell you how I use it for this particular purpose.

On the “front” of the “flash-card,” (I’m using quotes because these aren’t really cards and there isn’t really a “front,” there’s just a particular field you fill in with information) I put the name of the trick.

On the “back” of the card, I input the following things:

The set-up for the trick (if there is one)

The most basic steps to the trick.

Any presentational ideas or patter lines I want to make sure to include when performing.

So, I’d input the information in the program like this:

And I would create a different card for each trick in my repertoire. Those individual cards form a deck. And I practice my repertoire by opening the app on my iphone, going to that “deck” and practicing whichever card(s) it gives me for that day.

It will provide me with the front of the card by itself at first. So it will just give me this:

So that tells me to practice the Ambitious Card. I’ll run through the routine quickly, making sure I have all the beats down.

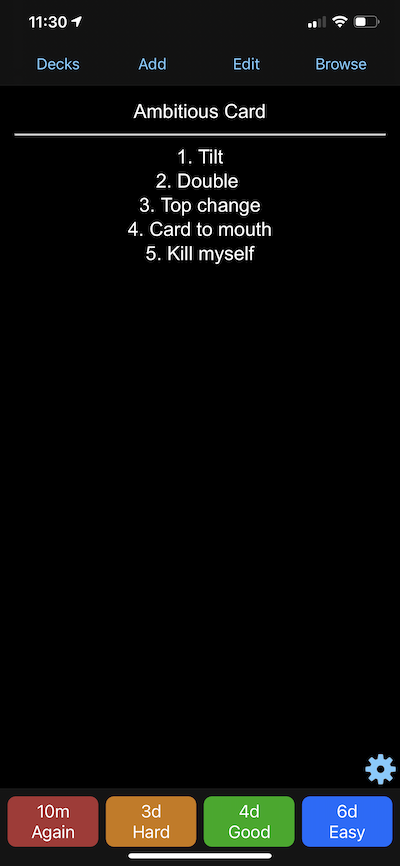

When I’m done (or if I get stuck), I’ll tap the screen to see the back of the card.

You’ll notice there are four buttons at the bottom of the screen.

If I screw the trick up or I can’t remember the set-up or whatever the case may be, I’d hit the red button and the card would go back into today’s stack to be done again.

If I got through the trick but it required more thought or effort than I would want it to in a real performance, I’d hit the orange button that says “Hard” and this card would come back into the stack in three days.

If I got through the trick fine I’d hit the green button and the trick would come back into the stack in four days.

For the purposes of practicing my repertoire, I don’t use the blue button.

The thing to understand is that the time periods associated with the buttons aren’t static. They change based on how well you’ve done with that card over time. So pressing the green button in this instance would bring back the card again four days later. The next time it comes around the green button would push the card like 7 days later, then 10, then 14, then 20, and so on. Similarly if you keep barely getting through the trick then it’s going to wait less and less time to bring that card forward each time. And if you screw up the trick or forget how to do it, then it’s going to start you back at the very beginning of the cycle where you’ll do the card today, again tomorrow, then a couple days after that, and so on.

If you’re really on top of a trick, then theoretically the interval between it showing up in your cards to practice on a given day could be pushed to months or years. You probably don’t want that to happen. Even if you know a trick perfectly, it’s good to be reminded of it and run through it once every couple months or so. So you’ll probably want to set the “max interval” for cards in your Repertoire Deck to two or three months at the most. That way you’re touching every trick at least 4-6 times per year (and much more frequently if you haven’t already mastered them).

One thing to keep in mind is that you don’t want to dump all your tricks into this program at once. If you do that, then all the cards in your practice database will be on identical intervals and tomorrow you’ll have 100 tricks you have to practice. Instead what you want to do is add one trick a day (if your repertoire is already established) or if you’re currently building your repertoire, then just add new tricks to this as you identify them. (I still wouldn’t add more than one per day.)

Once a day I fire up the app and run through the flash cards it has for me to process that day. It’s only a few cards at most. I’ll go through each trick and then hit the button to designate if I need to do the trick again, if it was hard, or if it went good. And that’s pretty much all there is to it, I think.

To be clear, I only use this program to help me practice. While I keep a barebones outline of the effect on the flash card, that’s just to be used as a quick reminder. The full catalog of my repertoire with all the details and information for each trick is in my Notion database, which I described in a couple of posts last year.