The Fitzkee Structure

/In last week’s Taxonomy post, I included Dariel Fitzkee’s list of the various types of magic effects.

Production (appearance, creation, multiplication)

Vanish (disappearance, obliteration)

Transposition (change in location)

Transformation (change in appearance, character or identity)

Penetration (one solid through another)

Restoration (making the destroyed whole)

Animation (movement imparted to the inanimate)

Anti-gravity (levitation and change in weight)

Attraction (mysterious adhesion)

Sympathetic Reaction (sympathetic response)

Invulnerability (injury-proof)

Physical Anomaly (contradictions, abnormalities, freaks)

Spectator Failure (magician's challenge)

Control (mind over the inanimate)

Identification (specific discovery)

Thought Reading (mental perception, mind reading)

Thought Transmission (thought projection and transference)

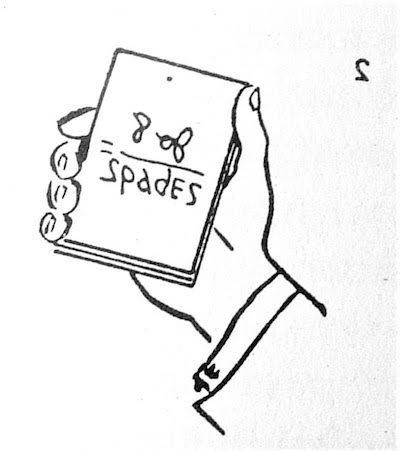

Prediction (foretelling the future)

Extrasensory Perception (unusual perception, other than mind)

While I don’t see too much value in the list as just a categorization of magic tricks, I think you could utilize the list as part of a dramatic structure for a long-running “storyline” in your magical endeavors.

I’ve suggested in the past that creating some continuity to your magic performances is a powerful way to get people hooked into seeing and hearing about your tricks. If everything is just some stand-alone piece of magic, there’s nothing intrinsically keeping them interested from the trick you show them one day to another.

But let’s say you have a close friend, a spouse, a roommate, or whatever, that you see regularly. And what if you introduced this list to them as something you were tackling? Maybe as a personal project. Or maybe you need to work your way through this list before gaining acceptance into some secret society. Or you have to show proficiency in each of these areas before certain other secrets are revealed to you. You can make the story behind why you’re tackling this list as believable or outlandish as you like.

But now you have a structure that allows you to show them 19 tricks—perhaps over a year or two of time—that don’t need to be tied together in any way other than the over-arching storyline of you working your way through the list. They’re witnesses to you accomplishing this goal. It gives the magic tricks themselves a greater meaning.

To add some drama to it, there should be failures and setbacks along the way. For example, maybe vanishes just aren’t your thing. They don’t come naturally to you. So you place a half-dollar on your left palm and wave your right hand over it. “Can you still see it?” you ask. They can. You try it again. Still no luck. You skip it for now on the list. You try it again a couple of months later. It doesn’t vanish again. Sometime down the line, you try it with a peanut instead of a coin. “The lighter density might help,” you suggest. The peanut doesn’t vanish either. You continue working your way through the list in the meantime. Until one day you’ve finished everything but that goddamn vanish. “I’m just going to focus on it for the next week and see if I can get it,” you tell the person who has been with you through this journey.

The next time you see them, you place the coin on the palm of their hand and wave your hands over it and…

It’s still there.

Shit.

Okay. One more time. Slowly you wave your hands over the coin and it completely vanishes.

You let out a guttural grunt and slump down, resting your hands on your knees. “Fucking finally,” you exclaim.

That build-up makes it actually worth getting a Raven rigged up in your jacket to vanish the coin.

The Raven is a beautiful coin vanish, but it’s over so quickly. This structure turns it into a 17-month coin vanish. It has so much more weight to it.

You might think, “Ah, my wife barely likes magic tricks. She’s not going to want to watch me work my way through this list.”

Okay, fine. But does she like you? This structure makes the story about reaching a goal, which everyone can relate to. Not just random tricks.

You might not like weightlifting, but if your best friend asked you to spot him for a few minutes once a month while he worked on achieving a personal goal for his deadlift, you’d go out in the garage and help him out. And you’d be invested (unless you’re a total self-absorbed piece of shit). And when he finally reached his goal of deadlifting double his body weight, you’d be psyched even if you never gave one second’s thought to weightlifting ever again.

Creating a broader narrative for your tricks to live within will ratchet up the interest level of anyone who watches this play out. The Fitzkee list is a great structure to do this.