"I can make those mountains bigger," I tell you. You disagree. The mountains are the mountains, you can't change their size.

So we drive to the base of the mountains. "Look up," I say, "The mountains are now bigger. What was once a jagged line on the horizon now towers thousands of feet above and is thousands of miles in length. You now feel dwarfed by something you previously could have blocked out of view with a playing card. I made them bigger."

You would vary rationally argue that I didn't make the mountains bigger, just your perception of them. And that's true enough, but when we're talking about time, your perception of it is all that matters.

So how do we make time bigger (longer/slower) and more expansive like we did with the mountains? We need to get closer to it. You can't physically get closer to time, of course, but one of the effects of being closer to something is being able to see it in more detail. So to make the life we've lived seem longer and richer we need to see it in more detail. So to slow time we need to create details -- moments that stand out from the constellation of the everyday.

Details are: taking part in new experiences, meeting new people, trying new activities, learning new things. If you pack your life with these you get a much more detailed view of the time that has passed. It seems closer, richer, and slower. We all understand this when we look at time in a micro sense. That day you spent exploring NYC -- seeing the sites, trying new foods, watching a Broadway show -- likely feels fuller and more rewarding and "larger" in your memory than that day you had off from work where you watched a Law and Order marathon and ate a tray of brownies (although that can be great too if it's not the norm).

This is certainly not a new concept. I'm only offering a new way of looking at it that might resonate with some people and some practical tools to help achieve this at the end of this post.

One of the people who put it best, and most succinctly, was Joshua Foer in his book, Moonwalking with Einstein.

Monotony collapses time; novelty unfolds it. You can exercise daily and eat healthily and live a long life, while experiencing a short one. If you spend your life sitting in a cubicle and passing papers, one day is bound to blend unmemorably into the next - and disappear. That's why it's so important to change routines regularly, and take vacations to exotic locales, and have as many new experiences as possible that can serve to anchor our memories. Creating new memories stretches out psychological time, and lengthens our perception of our lives.

The problem is that for a long time our culture didn't respect a life full of details. And I would say that many, if not most, people are still in that mindset. "He met his wife at age 18 and then spent 45 years working for Xerox," is seen as a success story instead of what it's at least as likely to be: a genuine, fucking nightmare.

I'm not saying you need to get a divorce or quit your job. I'm just saying society doesn't put a ton of value on those things that create a detailed life. It's almost seen as immature if you're an adult and you seek novelty and adventure. So recognize that perception is working against you.

Here are two techniques that I've used to "stretch out psychological time" and "lengthen the perception of my life," as Joshua Foer puts it.

Easy Mode

If you were leading a more vibrant, varied life, what time of day would you most likely be involved in some new activity or endeavor? Let's say you sleep a normal schedule and have a regular day job. If that's the case, then maybe 7:30 at night is when you have the most potential for varied activities. Go into your phone and set an alarm to go off every night at 7:30. Then, every day when the alarm goes off, you make note of what you're doing and you write it in a journal or put it online somewhere. This isn't a diary. I mean, it is, kind of. But it's just a diary of what you're doing at 7:30 every night.

Eventually you're going to feel pathetic if you have a journal or a twitter feed or a spreadsheet on your computer filled with the exact same boring thing day after day. At some point you'll start planning some interesting things just so you can write something different. You don't want to die and have your grandkids uncover a foot-locker with 18 years worth of journals in it and for every day of those 18 years you've written the same thing, "7:30 - Watched Jeopardy." Is that what you want your legacy to be? Your family arguing for years to come if you were a psychopath or just feeble-minded?

Keeping a record will just be very gentle encouragement that you might want to plan to have something interesting to write for that day. Thus, making memories, adding detail.

Hard Mode

Think about the moments you remember in your life, the big and small ones. Think about the things you remember from the last week, last month, last year, last decade, and beyond. Now try and bundle them into some very loose categories in regards to what those things have in common.

For me, my memorable events tend to fall into one of these categories:

- Doing something for the first time (whether an achievement of some kind or just trying something new/going somewhere new)

- Meeting someone for the first time

- Taking part in an activity that could only occur on that specific day (a concert, a sporting event)

- Interacting with someone I hadn't seen for a long time

- Doing something related to some celebration or holiday

- Enjoying some seasonal activity in nature (snowboarding, going to the beach)

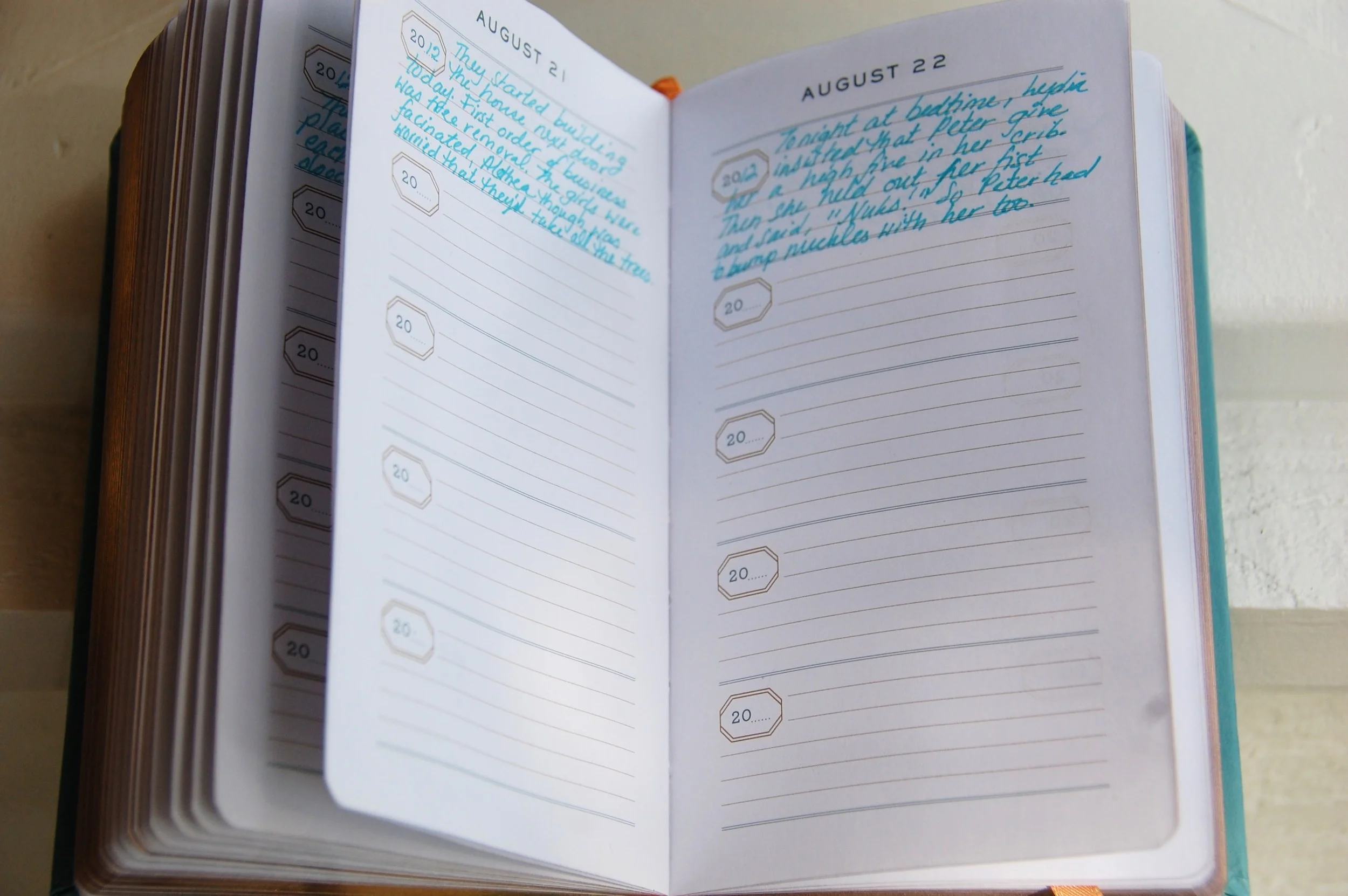

Now go get yourself one of these journals. This is a "one line a day" journal which, as you might expect, is a journal set up so you write one line per day. Not only that, but it's a five year journal. It doesn't cycle through the year 5 times. Each page is devoted to a date and there are five entry slots on each page. So you write the entries for 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 all on the same page for April 11th, or whatever. This is a nice way to see what you were up to on that date over time.